Staff Photo

Breaking projects into multiple phases helps ease the stress and financial strain those projects can cause

By Michael Peyton, SGI Range and Wildlife Conservationist

Implementing conservation practices in the West can quicky become overwhelming. The time and cost is large on thousands, and sometimes hundreds of thousands, of acres. Both public and private land is often included. New practices might be involved. Breaking projects into multiple phases helps ease the stress and financial strain those projects can cause.

When trying to accomplish a project at those scales you need to coordinate with different agencies such as the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS), Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and U.S. Forest Service (USFS) to name a few. That takes extra time to coordinate work for funding, cultural clearance and National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) review.

It can take over a year to get the all the proper clearances before work can commence. Most agencies have funding pools that will help landowners with a cost-share incentive to complete wildlife habitat improvement projects, but the funding amount and timing varies year to year.

Many western habitat projects are broken into phases simply because of the size. Most projects are completed at a landscape level. Examples include removing pinyon juniper from a mountainside or seeding thousands of acres after a wildfire. These projects take an immense amount of time and effort to locate funding and coordinate with agencies.

Another important phase in many projects is to experiment with a smaller acreage before going all-out. One example might be trying a new seed mix or food plot practice. It is better to learn from mistakes and perfect methods, then take the newfound knowledge and apply it to second or third phases.

Grouse Creek Corridors

One example of a phased approach is in the Grouse Creek Mountains in far northwestern Utah. The Dry Basin Complex is well known for lekking sage grouse in the spring. These grouse come from miles away, including neighboring states. Recently I contracted a project, with financial assistance from USDA-NRCS and Utah WRI funds, on the edge of the Dry Basin Complex to create a treeless corridor from east side of the Grouse creek range to the west side.

The project consists of about 1,200 acres of native range seeding applied via plane in early winter. Large excavators outfitted with bullhog attachments to grind trees into mulch showed up the following spring to remove 1,200 acres of encroaching pinyon juniper at about seven acres per machine per day. This work was the final phase or puzzle piece of a larger program connecting several previous restoration programs together and eliminating habitat fragmentation.

Raft River Project

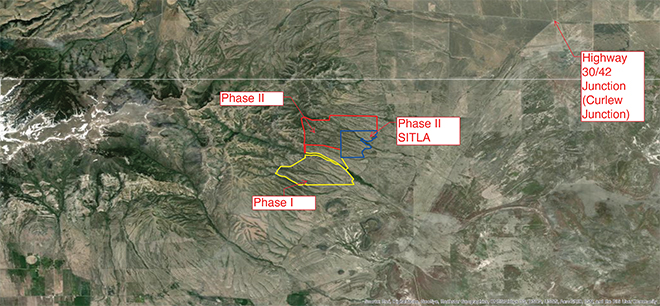

Another example of a phased project is in the foothills of the Raft River Range located on the Utah/Idaho border. Last year we completed about 1,300 acres of pinyon juniper work with bullhogs. The project area is private land boarder by USFS and state land. We are hoping to contract another 1,000 acres of private land and a full section of state land to bring the total acreage to 1,600.

Michael Peyton is an SGI Range and Wildlife Conservationist

This story originally appeared in the 2022 Summer Issue of the Pheasants Forever Journal. If you enjoyed it and would like to be the first to read more great upland content like this, become a member today!