For pheasants, habitat is king. And sometimes you have to decide where best to put it.

By Scott Taylor

Part 3 of a Series

Pheasants are most abundant where their preferred habitats are common and well interspersed. Armed with some basic biology and an assessment of the habitats in shortest supply, a pheasant manager can prescribe a science-based remedy for a landscape’s low bird numbers, though factors beyond her control (examples include Farm Bill program constraints and landowner profitability trade-offs) usually dictate whether that prescription can or will be filled.

But what if the question is not what to do, but where best to do it?

Assuming we have some money to invest in habitat and our goal is to produce the most pheasants per acre within a given state, are we better off putting more habitat in areas where pheasants are already abundant or where they are relatively scarce? State wildlife agencies regularly face this question. But for all the past research we have done, very little of it is directly applicable to an answer.

When asked what science issue they most wanted to cooperate on, the agencies involved with the National Wild Pheasant Conservation Plan named this one. The U.S. has lost about 17 million acres of Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) grasslands since 2007, and if we ever get the opportunity to add some back, it would be great to help the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) nudge that habitat into the best possible places in each state. The states also want to use their own resources to bring habitat, pheasants, and hunters together as efficiently as possible, and this topic is a key piece of that puzzle.

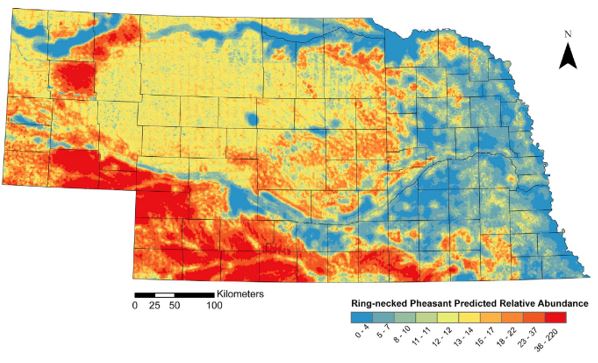

A solution requires lots of field measurements of habitat variables and associated pheasant abundance, which are then used to create a predictive mathematical model relating local habitat conditions to population size. Within a state, the model can then be used to estimate population sizes anywhere that relevant habitat data are available, with the range-wide results usually converted into a “thunderstorm” map (Figure 1 following). The greater the number and variety of original field measurements in time and space, the more reliable the map’s predictions usually are.

Figure 1. An example of a habitat model-based population estimation map; this one depicts relative abundance rather than abundance per acre of habitat. For details, see Jorgensen et al. (2014).

Figure 1. An example of a habitat model-based population estimation map; this one depicts relative abundance rather than abundance per acre of habitat. For details, see Jorgensen et al. (2014).

Wherever the model predicts the highest pheasant numbers per acre of habitat, that is where (in theory) adding more habitat should provide the greatest returns. Ideally, the model should be validated by comparing its predictions to more observations in the field, and then updated based on those new data.

This process has been called “strategic habitat conservation,” and the resulting map of predicted densities is an example of a “decision support tool.” Landowner receptiveness, access possibilities, and proximity to hunters also influence where best to work, and sometime these factors can be mapped and overlaid, as well.

Although these tools are potentially game-changing, each step in the process can be costly, and each dollar spent on estimation is one less that could be spent on habitat or hunter access (which isn’t always true depending on what funds are being used, but opportunity costs are always in play).

In an era where many organizations are scrambling to respond to habitat and hunter participation losses, no state that I am aware of has been able to make such a long-term investment in maximizing its management efficiency. Multi-state collaboration and recent technological advances could help reduce costs, however.

Despite being its highest science priority, it may take a while for the National Wild Pheasant Conservation Plan partnership to line up the funding, staff time and expertise necessary to launch the project.

In the meantime, don’t worry: For we who love pheasants, habitat still provides benefits wherever we get the opportunity to invest. Keep doing everything you can to improve what the habitat we have, and make more of it on the landscape.

Next month: How the National Pheasant Plan partners are answering the question: “How much CRP do we really need?”

Prior to becoming the National Wild Pheasant Conservation Plan Coordinator, Scott Taylor worked for the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission as an upland game biologist, wildlife research section leader, and Wildlife Division chief. He earned a B.S. in Wildlife Biology from Kansas State University, a M.S. in Range and Wildlife Management from Texas A&M University-Kingsville, and a Ph.D. in Wildlife Ecology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He lives in Manhattan, Kansas and is a PF Life Member.